A Tribute to Athol Fugard: The Voice of Apartheid South Africa

In January 2010, a serendipitous encounter occurred at a coffee shop in Cape Town, where noted playwright Athol Fugard was observed savoring a simple cup of coffee. Fugard, known for his profound contributions to South African theater, especially regarding the narratives surrounding apartheid, was approachable, displaying a genuine warmth that belied his monumental status in the arts.

An Ordinary Man with Extraordinary Insights

As Fugard passed away recently, reflections on his character reveal much about the man behind the plays. He embodied the duality of being both extraordinary and relatable. His enthusiasm for humanity and an unwavering belief in people’s potential were evident during conversations. However, he did not shy away from exploring the darker facets of both society and himself—exemplified in his renowned play, “‘Master Harold’… and the Boys,” which draws from his personal experiences of racial tensions.

A Masterful Storyteller

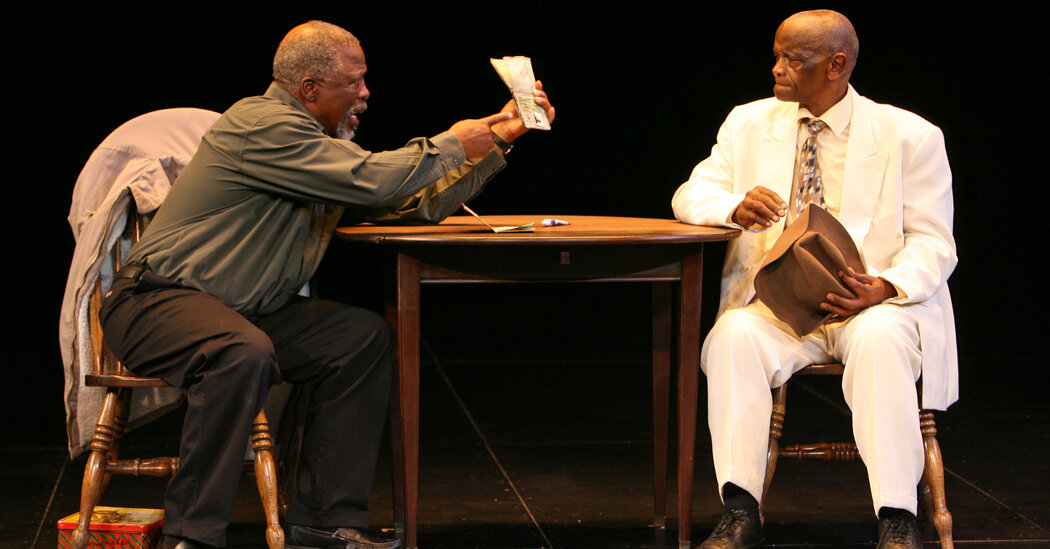

The late theater critic Frank Rich recognized Fugard’s ability to convey deep moral truths through intimate storytelling. In his 1982 review of “Master Harold,” Rich observed how Fugard’s technique involved meticulous attention to the small details that defined the characters’ lives.

Early Encounters with Fugard’s Work

Fugard’s influence permeated the South African theater landscape since the early 1980s, with significant works such as “Sizwe Banzi Is Dead,” co-written with Winston Ntshona and John Kani. This play depicts a man adopting another’s identity to escape the oppressive passbook laws governing employment in apartheid-era South Africa—a narrative filled with poignant humor that starkly highlights the brutal realities of systemic racism.

Emotionally Charged Stories

For an audience shaped by the realities of apartheid, witnessing “Sizwe Banzi Is Dead” was a profound moment of reckoning. The impact of Fugard’s work resonated personally, as it conjured memories of living within a society marked by racial injustice. The emotional depth of his characters blended humanity with the painful truths of their circumstances, encapsulating the struggle against an oppressive regime.

The Fugard Theater: A Cultural Landmark

In 2010, Fugard returned to Cape Town to rehearse “The Train Driver,” just before its debut at the Fugard Theater—a venue named in his honor by producer and philanthropist Eric Abraham. Located in District Six, a once-diverse neighborhood now marked by the scars of apartheid, the theater aimed to reclaim its lost heritage. On the theater’s opening night, Fugard stated, “You will be sitting in the laps of the ghosts of the people who couldn’t be here.”

A Focus on Forgotten Lives

Fugard’s oeuvre seeks to give voice to the silenced and the forgotten. His best-known plays, such as “Blood Knot,” “Boesman and Lena,” “The Island,” and “The Road to Mecca,” rigorously scrutinize how race shapes personal relationships within an apartheid context while maintaining a core sense of humanity. Abraham aptly noted Fugard’s gift for delivering moral clarity, pivotal in navigating the complexities of both South African and global social landscapes.

A Legacy of Humanity

After the establishment of the Fugard Theater, Fugard settled back in South Africa, oscillating between his homes in New Bethesda and Stellenbosch. His modesty, lack of formal training, and dedication to authentic storytelling established him as an outsider artist. Despite his local roots, his narratives resonate universally, underscoring the intrinsic value of every human life.

In reflecting on his life, many recall Fugard’s hospitable nature, often concluding conversations with an invitation for a glass of wine. His legacy endures, urging all to confront the past and strive for empathy and understanding in an often harsh world.